贲门失弛缓症与癌症的预防和监测

介绍

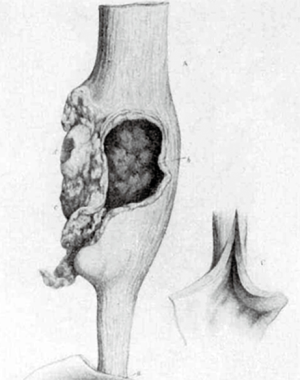

贲门失弛缓症与食管癌(EC)之间的关联早已得到认可。这种关联于1872 年被首次描述,当时一位名叫 Charles Hilton Fagge 的英国医生描述了一位 84 岁患者的病例,该患者有40年的吞咽困难史,在他的食道扩张部分形成了肿瘤(图1)[1]。从那时起,一些研究陆续地表明了这种关联性的存在[2-5]。

几个假定的因素被认为是导致这种关联的原因,包括唾液引起的化学刺激和继发于食管腔内的残存食物的分解可能导致食管上皮的异型增生[6],食道内细菌生长导致的亚硝胺增加[7],以及遗传因素[8]。

贲门失弛缓症与癌症风险

贲门失弛缓症患者发展为食管鳞状细胞癌(SCC)的实际概率是未知的,在文献中的报道也并不一致,发生率从0到33%[9-14]不等。Eckardt等人在一篇论文中回顾了至少5年随访的临床研究,他们的研究报道的发病率可能更接近实际情况,为0到7%[15]。

虽然一些较早的研究没有显示贲门失弛缓症患者的食管癌病例[9,16,17],但最近的两项Meta分析显示,贲门失弛缓症患者中SCC的发生率从1.36/1000患者-年[18]到3.12/1000患者-年[19]不等,发生率分别为1.5%和2.8%。根据国际癌症研究机构(IARC)的数据,这些比例分别是普通人群患食道鳞状细胞癌风险的15倍和34倍[20]。此外,这些研究表明,癌症的发生很少出现在发病的头5年,但在发病10年之后概率显著增加。另一项Meta分析发现,接受贲门失弛缓症治疗的患者的发病率为2.05/1000 患者-年,特别是在患病10年后[21]。因此,根据国际食道疾病学会(ISDE)的指南,贲门失弛缓症患者在最初接受治疗的10年内发展为SCC的风险会适度增加[22]。

有证据表明贲门失弛缓症患者食管腺癌(EAC)的发病率比普通人群高出6倍[19],这一事实可以通过治疗贲门失弛缓症导致胃食管反流病(GERD)和Barrett食管(BE)的致癌作用来解释[23,24]。事实上,据报道,贲门失弛缓症经球囊扩张治疗后Barrett食管高达9%[25],经口内镜下食管括约肌切开术后Barrett食管为5.5%[26]。在Heller贲门肌层切开术和胃底折叠术(HMF)治疗后很少会发生Barrett食管,常常在手术治疗失败后的很长一段时间内才会出现[27,28]。然而,在未经治疗的患者中也有发展为Barrett食管的病例[29]。这种现象的原因尚不清楚,主要的假设是,食物和唾液潴留引起的慢性炎症可能引发导致BE的一连串事件[30]。然而,贲门失弛缓症和食管腺癌之间的真正联系是有争议的,且仍然未知。

这种风险、患病率和发病率的变化可能与每项研究中贲门失弛缓症的随访时间有关[11,19,21],因为在长期研究中观察到肿瘤的发病显著增加[15]。

监测和预防

监测在贲门失弛缓症中的作用是一个讨论了几十年的话题,但没有达成共识,也存在一些争议[30-32]。贲门失弛缓症患者发生食管癌的相对风险高于一般人群(10~50 倍),但绝对风险相对较低(1.5%~3%),这表示每年的发病率为0.1%~0.3%[18,19]。这意味着我们需要对贲门失弛缓症患者群体进行大约 400 次内窥镜检查才能发现 1 例食管癌[11]。此外,在这个人群中,食管癌的早期诊断和预后的数据存在矛盾[10,14,15]。这种认为内镜定期监测可能不会影响肿瘤预后的看法[10,33]使得统一管理和制定监测指南变得更加困难。事实上,重要的学会如国际食管疾病学会(ISDE)[22]、美国胃肠内镜学会(ASGE)[34]和美国胃肠病学会(ACG)[35]不建议对这些患者进行特定的常规监测,只考虑10~15年疾病期间内镜检查的可能性。类似的建议可以在最近的论文中找到[15,36,37]。

另一方面,0.3%/年的风险与无异型增生[38]或低度异型增生[39]的 Barrett 食管恶性肿瘤的风险相当,而在这些特定情况下,通常建议进行监测。尽管存在类似的风险,但建议是不同的。首先,贲门失弛缓症是一种非常罕见的情况。虽然贲门失弛缓症的发病率约为十万分之一[40],但约10%的GERD患者可能存在BE[41]。第二,食管癌可在贲门失弛缓症的初始症状发现 40 年后出现[1,15,18,19];第三,Barrett食管有可改变的先决条件。这些因素使得证据更加可靠,标准化程度更高,评估效率更高。

另一个重要的考虑是食管癌通常在贲门失弛缓症中诊断较晚,因为由肿瘤引起的吞咽困难可能被误以为是贲门失弛缓症原有的症状。 因此,贲门失弛缓症中的大多数食管癌被诊断时为晚期,预后较差[19,42,43]。

年龄[11,15,19]、男性[10,11,23]、贲门失弛缓症发生时间[10,11,15,18,19,23]、Chagas病[19]等因素被认为是食管癌的危险因素。其他因素,如贲门失弛缓症治疗的类型(内窥镜与外科手术)[18,29,31]、酒精摄入和吸烟[10],看似合理但证据较少。

尽管尚未达成共识,但从贲门失弛缓症发病的第 10 年开始,每 3~5 年考虑进行内镜检查似乎是合理的,尤其是男性、老年人、Chagas病,或存在相关的危险因素,如酒精、吸烟和内镜治疗贲门失弛缓症。然而,一些问题,如开始监测的时间、检查之间的时间间隔、内窥镜技术的类型(白光成像、染色内镜或内镜窄带成像术)和连续活检的需求仍未得到解答,需要进一步研究以获得更强有力的建议。

结论

贲门失弛缓症是公认的食管癌的危险因素,无论是鳞状细胞癌还是腺癌。必须告知患者食管癌的风险,尤其病程超过10年(即使是接受治疗后)。使用增加胃食管反流风险的方法治疗贲门失弛缓症(肉毒毒素注射、球囊扩张和经口内镜下食管括约肌切开术)应被认为是Barrett 食管的危险因素。

对于病程超过10年的患者,尤其是存在其他相关危险因素的患者,可以考虑进行定期监测。

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Ms. Cathy Williams, Archives Services Manager from the Archives & Research Collections, King’s College London Archives for her kind attention and authorization to reproduce Figure 1.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the the editorial office, Annals of Esophagus for the series “How Can We Improve Outcomes for Esophageal Cancer?”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aoe.2020.02.01). The series “How Can We Improve Outcomes for Esophageal Cancer?” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. FAMH served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Fagge CH. A case of simple stenosis of the oesophagus, followed by epithelioma. Guys Hosp Rep 1872;17:413-21.

- Rake G. Epithelioma of the oesophagus in association with achalasia of the cardia. Lancet 1931;2:682. [Crossref]

- Kornblum K, Fischer LC. Carcinoma as a complication of achalasia of the cardia. A J R Am J Roentgenol 1940;43:364.

- Ellis FG. Natural History of achalasia of the cardia. Proc R Soc Med 1960;53:663-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Just-Viera JO, Morris JD, Haight C. Achalasia and esophageal carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 1967;3:526-38. [PubMed]

- Chino O, Kijima H, Shimada H, et al. Clinicopathological studies of esophageal carcinoma in achalasia: analyses of carcinogenesis using histological and immunohistochemical procedures. Anticancer Res 2000;20:3717-22. [PubMed]

- Pajecki D, Zilberstein B, Cecconello I, et al. Larger amounts of nitrite and nitrate-reducing bacteria in megaesophagus of Chagas’ disease than in controls. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:199-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manoel-Caetano FS, Borim AA, Caetano A, et al. Cytogenetic alterations in chagasic achalasia compared to esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2004;149:17-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chuong JJ, DuBovik S, McCallum RW. Achalasia as a risk factor for esophageal carcinoma. A reappraisal. Dig Dis Sci 1984;29:1105-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leeuwenburgh I, Scholten P, Alderliesten J, et al. Long-term esophageal cancer risk in patients with primary achalasia: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2144-9. [PubMed]

- Sandler RS. The risk of esophageal cancer in patients with achalasia. A population-based study. JAMA 1995;274:1359-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zaninotto G, Rizzetto C, Zambon P, et al. Long-term outcome and risk of oesophageal cancer after surgery for achalasia. Br J Surg 2008;95:1488-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet 2010;375:1388-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brücher BL, Stein HJ, Bartels H, et al. Achalasia and esophageal cancer: incidence, prevalence, and prognosis. World J Surg 2001;25:745-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eckardt AJ, Eckardt VF. Editorial: cancer surveillance in achalasia: better late than never? Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2150-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arber N, Grossman A, Lurie B, et al. Epidemiology of achalasia in central Israel. Rarity of esophageal cancer. Dig Dis Sci 1993;38:1920-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farr CM. Achalasia and esophageal carcinoma: is surveillance justified? Gastrointest Endosc 1990;36:638-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gillies CL, Farrukh A, Abrams KR, et al. Risk of esophageal cancer in achalasia cardia: A meta-analysis. JGH Open 2019;3:196-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tustumi F, Bernardo WM, da Rocha JRM, et al. Esophageal achalasia: a risk factor for carcinoma. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Globocan. Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide, Version 1.0. lARC Cancer Base No. 5. Lyon: lARC Press, 2000;2001.

- Markar SR, Wiggins T, MacKenzie H, et al. Incidence and risk factors for esophageal cancer following achalasia treatment: National population-based casecontrol study. Dis Esophagus 2019;32:doy106 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zaninotto G, Bennett C, Boeckxstaens G, et al. The 2018 ISDE achalasia guidelines. Dis Esophagus 2018;31. [PubMed]

- Zendehdel K, Nyren O, Edberg A, et al. Risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in achalasia patients, a retrospective cohort study in Sweden. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:57-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo JP, Gilman PB, Thomas RM, et al. Barrett’s esophagus and achalasia. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002;34:439-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leeuwenburgh I, Scholten P, Calje TJ, et al. Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma are common after treatment for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:244-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Teitelbaum EN, Dunst CM, Reavis KM, et al. Clinical outcomes five years after POEM for treatment of primary esophageal motility disorders. Surg Endosc 2018;32:421. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Csendes A, Braghetto I, Burdiles P, et al. Very late results of esophagomyotomy for patients with achalasia: clinical, endoscopic, histologic, manometric, and acid reflux studies in 67 patients for a mean follow-up of 190 months. Ann Surg 2006;243:196-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Di Corpo M, Farrell TM, Patti MG. Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy: A Fundoplication Is Necessary to Control Gastroesophageal Reflux. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2019;29:721-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cantù P, Savojardo D, Baldoli D, et al. Barrett’s esophagus in untreated achalasia: ‘guess who’s coming to dinner’ first. Dis Esophagus 2008;21:473. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nesteruk K, Spaander MCW, Leeuwenburgh I, et al. Achalasia and associated esophageal cancer risk: What lessons can we learn from the molecular analysis of Barrett's–associated adenocarcinoma? Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2019;1872: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brossard E, Ollyo JB, Fontolliet CH, et al. Achalasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: is an endoscopic surveillance justified? Gastroenterology 1992;102.

- Wychulis AR, Woolam GL, Andersen HA, et al. Achalasia and carcinoma of the esophagus. JAMA 1971;215:1638-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ravi K, Geno DM, Katzka DA. Esophageal cancer screening in achalasia: is there a consensus? Dis Esophagus 2015;28:299-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hirota WK, Zuckerman MJ, Adler DG, et al. ASGE guideline: the role of endoscopy in the surveillance of premalignant conditions of the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:570-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1238-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramai D, Lai JK, Ofori E, et al. Evaluation and Management of Premalignant Conditions of the Esophagus: A Systematic Survey of International Guidelines. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019;53:627-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chaber-Ciopinska A, Kiprian D, Kawecki A, et al. Surveillance of patients at high-risk of squamous cell oesophageal cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2016;30:893-900. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wani S, Falk G, Hall M, et al. Patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus have low risks for developing dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:220-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wani S, Falk GW, Yerian L, et al. Risk factors for progression of low-grade dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011;141:1179-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sadowski DC, Ackah F, Jiang B, et al. Achalasia: incidence, prevalence and survival. A population-based study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22:e256-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schlottmann F, Patti MG, Shaheen NJ. From Heartburn to Barrett’s Esophagus, and Beyond. World J Surg 2017;41:1698-704. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loviscek LF, Cenoz MC, Badaloni AE, et al. Early cancer in achalasia. Dis Esophagus 1998;11:239-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peracchia A, Segalin A, Bardini R, et al. Esophageal carcinoma and achalasia: prevalence, incidence and results of treatment. Hepatogastroenterology 1991;38:514-6. [PubMed]

余振

单位:首都医科大学附属北京同仁医院胸外科

学术任职:北京医学会胸外科学分会青年委员;

中国研究型医院学会加速康复外科专委会胸外科学组北京青年专家组副组长;

中国医疗保健国际交流促进会胸外科分会青年委员会委员;

中国医疗保健国际交流促进会胃食管反流多学科分会青年委员会委员;

美国耶鲁大学医学院访问学者。

(更新时间:2021/8/1)

周卧龙

中南大学湘雅医学院本科毕业,中南大学湘雅医院胸外科硕士、博士毕业,美国贝勒医学院(Baylor College of Medicine)联合培养2年。长期从事胸外科肺癌、食管癌的基础与临床研究,对食管疾病相关的临床研究与外科技术进展有浓厚的兴趣。(更新时间:2021/8/1)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Del Grande LDM, Herbella FAM, Katayama RC, Landini Filho LS, Mocerino J, Ferreira AEP. Achalasia and cancer prevention and surveillance. Ann Esophagus 2020;3:19.