肥胖食管癌患者的食管切除术

肥胖与癌症

世界上人口聚居的国家中超重和肥胖是导致疾病和死亡的常见因素[1]。全世界肥胖的罹患率在过去50年里几乎翻了3倍:1975—2014年间,男性年龄标准化肥胖罹患率从3.2%增加到10.8%,女性从6.4%增加到14.9%[2]。

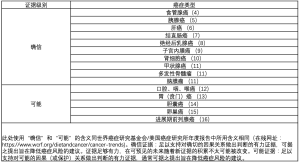

肥胖是部分慢性疾病(如高血压、2型糖尿病、血脂异常、冠状动脉疾病)明确的危险因素。过去十年研究显示肥胖不仅是某些癌症的易感因素[3](表1),还是某些癌症的预后危险因素[17,18]。因此,国际癌症研究机构(International Agency for Research on Cancer,IARC)于2002年出版专著,提出体重控制和躯体锻炼可以作为癌症的预防策略[19]。

Full table

肥胖与食管癌

据报道,美国食管癌的年诊断例数为17 605,食管癌相关的年死亡例数为16 080[20]。GLOBOCAN数据库数据统计显示全球新发食管癌预计为每年572 034例,食管癌相关死亡预计为每年508 585例[21]。

有趣的是,作为食管癌的两种主要组织学类型,腺癌和鳞癌发病率的时间变化趋势有所不同。

在大多数西方国家,由于已知危险因素(如超重和肥胖)罹患率的增加,食管腺癌的发病率在急剧上升[22]。然而这些国家食管鳞癌的发病率则在稳步下降,原因是烟草和酒精使用的长期减少。肥胖已被证明与食管鳞癌的发生存在矛盾的、反向的联系[23]。

肥胖与食管腺癌之间强烈正相关性的机制尚未得到充分阐明。从病理生理学角度来看,两个等地位的假设包括腹部肥胖的机械效应引发胃食管反流病[24]及肥胖相关的代谢通路改变。胃食管反流病是众所周知的引发食管腺癌癌前病变——Barrett食管的危险因素[25-27]。由于腹内压的机械性升高,胃食管反流病更常见于高体质指数(body mass index,BMI)人群[28-30]。

肥胖伴随有细胞增殖、凋亡和生长调节代谢通路的改变[31],而胰岛素抵抗、促炎细胞因子和脂肪因子可能在其中发挥重要作用[32-39]。然而,这些促炎进程与Barrett食管在促进食管化生、异常增生和最终癌变方面的相互作用方式仍有待阐明。

总之,超重人群罹患食管腺癌的风险是正常体重人群的1.5~2倍,而肥胖人群罹患食管腺癌的风险是正常体重人群的2~3倍[40]。

既往的广泛研究仍未明确揭示肥胖同食管鳞癌之间负相关的生物学机制[40]。这种关联性仅见于吸烟人群,而未见于既往吸烟或不吸烟人群,导致这一关联性本身存在争议[41]。考虑到吸烟是食管鳞癌的重要易感因素,此负相关性可能只是残留混杂因素作用的结果[42,43]。

肥胖患者的食管切除术

肥胖食管癌患者的手术治疗面临特殊挑战。

手术规划

肥胖患者获取术前影像学资料是有困难的,肥胖对成像的影响众所周知。

肥胖患者由于体重超过制造商规定的CT/MRI工作台承重限制或其身体周长超出机架直径,可能无法完成术前影像评估,这成为进一步手术的禁忌。

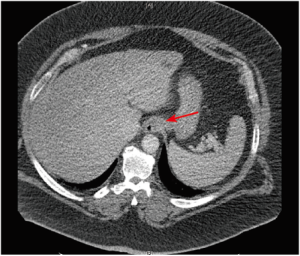

即使患者体重和周长适合进行CT扫描,过多脂肪组织相关的技术限制也将影响所获得图像的质量:光束穿透不足导致的噪声增加、视野受限及图像裁剪都是亟待解决的问题[44]。然而,有报道显示与同腹膜内脂肪组织稀少患者相比,腹膜内或腹膜后脂肪丰富的患者内脏器官结构的可视化程度更高。这是因为器官周边脂肪组织有助于提升CT勾画效果[44](图1)。

常用的MR扫描仪具有高信噪比和强梯度(1.5T),其重量限制为350磅(159 kg),直径限制为60 cm[45]。垂直开放式MRI允许的承重限制高达550磅(250 kg),但信噪比和梯度较低[45]。与CT扫描相似,肥胖患者接受MRI的局限性包括射频穿透和梯度强度改变、视野受限、扫描时间增加及射频能量在机架邻近皮肤的沉积[44]。CT和MRI的机器制造商每年都会进行设计革新以适应肥胖患者,肥胖对影像评估的限制可能在未来几年得到解决。

麻醉要点

择期食管癌手术麻醉管理的肺误吸风险较高,其应对措施包括单肺通气及精细的术后疼痛管理。

最大限度地降低食管癌患者肺误吸风险是至关重要的,特别是考虑到食管肿物导致的食管狭窄和动力异常将增加肺误吸基线风险。此外,肥胖患者由于腹内压升高将导致胃食管反流发生概率增加[46,47]。因此,术前禁食对于诱导全身麻醉是必须的[48]。预防措施还包括快速序贯诱导和插管技术,该技术已被证明可以保护气道并最大程度地降低误吸风险[49,50]。

肥胖患者的气道管理被认为具有挑战性的原因:首先,过多脂肪造成肺结构受限,导致功能残气量降低和通气-灌注不匹配[51-56];其次,肥胖可能导致相关的呼吸系统疾病,即气道高反应性[57-59]、睡眠呼吸暂停[60-62]和肥胖低通气综合征[63-65];最后,肥胖引起的药代动力学变化增加术后呼吸抑制风险。

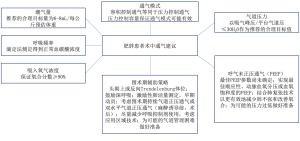

因此,麻醉前的规划应确定是否必须进行单肺通气,以及在现有的各种双腔气管插管和支气管阻断器中使用哪种器械。肥胖增加了通过单肺通气实现足够保护性通气的难度,但既往研究显示单肺通气是足够而有效的[66]。几项关于单肺通气的研究(尽管并非针对接受食管切除术的肥胖患者)建议采用潮气量为4~6 mL/kg预测(非实际)体重的肺保护策略[67-69],并建议采用肺复张策略以减少无效通气并增加氧合[70]。肥胖患者术中通气的实用建议见图2。

术后应细致规划疼痛管理。权衡胸椎硬膜外镇痛、椎旁阻滞、竖脊肌阻滞及其他局部麻醉方式以选择最佳的疼痛管理方案。考虑到患者可能会由于吸收不良、分布异常及清除率改变而出现药代动力学变化[71,72],麻醉药物剂量应根据体重做出必要调整。

术中注意事项和围术期管理

食管切除术适用于食管癌一线治疗或新辅助放化疗后,肥胖患者和正常体重患者之间并无差异,具体可参考最新版NCCN食管癌及食管胃交界部癌临床实践指南[73]。

本综述不涉及无手术适应证肥胖食管癌患者的管理。

脂肪过多和肥胖已被证明同普外及食管手术术后并发症增加有关[74]。有趣的是,既往研究显示肥胖患者食管切除术后长期生存结局更好[75-77]。最近的一项荟萃分析也印证了这一发现[78]。所以,肥胖不应被作为食管切除术的禁忌证。

肥胖患者进入手术室后,在术前、术中及术后均应得到手术规划、设备需求及护理人员等方面的特别关注。考虑到微创食管切除术可能需要更长的手术时间和更先进的技术要求,这些关注显得更为必要。打孔位置需要根据患者体型(苹果型对比梨型肥胖)定制。手术结束后缝合套管针孔要注意避免形成皮下血肿、褥疮或腹壁疝。躯干脂肪为著的患者,肥厚的脂肪层造成器械活动度下降,这可能会妨碍到达手术部位的腹腔镜器械和(或)机械操作手臂。此外,增多的腹膜内脂肪可能会显著改变器官的形状和位置,从而增加重要解剖结构的损伤风险。

尽管存在上述操作上的挑战,接受食管切除术的肥胖患者仍然可以明确地受益于微创技术。现有证据表明微创食管切除术同开放手术相比可降低肺部并发症发生率,并且不会对肿瘤学结局产生不利影响[79,80]。

围术期护理中应对肥胖患者进行仔细评估以防发生常见的外科并发症,特别是食管切除术相关并发症。患者需要应用全身抗生素预防感染性并发症,同时注重预防深静脉血栓形成及血栓栓塞。

术中放置空肠造口管有利于维持足够的肠内营养摄入。从术后第2天开始经造口管进行肠内喂养。逐渐增加摄入量直至达到喂养目标。有趣的是,Fenton等研究显示低体重(BMI <18.5 kg/m2)患者空肠造口管脱出概率高于肥胖(BMI >30 kg/m2)患者(优势比,7.56;95%置信区间,1.19-48.03)[81]。出于任何原因怀疑吻合口裂开时,均应进行吞钡或口服造影剂CT检查。肥胖患者发生吻合口瘘的风险较高,及时诊断是挽救患者的关键[78]。新发房颤时应考虑到吻合口瘘可能,特别是在罹患糖尿病的肥胖患者中。此类患者吻合口瘘发生率高于未合并糖尿病的肥胖患者[82]。

总而言之,外科医生应增强对肥胖患者手术并发症的警惕性,确保在整个围术期对合并症进行审慎的管理。

减重手术有用吗?

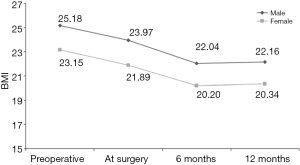

食管切除术后,大多数外科医生使用管胃代替食管以恢复胃肠道的连续性。替代器官还包括结肠或空肠并进行Roux-en-Y重建。这与减肥手术在概念上有显著重叠。有趣的是,Ouattara等研究了食管切除术后的体重减轻动力学特征[83]。追踪BMI随时间的变化,他们发现食管癌手术似乎有着显著的减重效果(图3)。

他们还重点评估了食管切除术前后的营养不良状况,主要评估指标是非主动的体重减轻,这是食管切除术后6个月内最明显的副作用之一[84]。结果显示术前超重和肥胖是食管切除术后营养不良的独立危险因素[85,86]。这些患者的营养状况需要得到特别关注。根据我们的经验,一个有经验的减重外科医生应该加入到肥胖食管癌患者多学科诊疗团队中——决定是否在食管切除术前进行减重手术时必须考虑到患者的BMI、合并症、肿瘤情况和心理状态。

事实上,接受过胃旁路分流手术的患者可以安全地接受食管切除术(微创模式下也一样)——因为它具有良好的耐受性和技术上的可行性,并实现可接受的肿瘤学结局[87]。虽然食管切除前实施减重手术的作用尚未得到充分研究,Roux-en-Y胃旁路分流将是这些患者减重手术的首选,这保证胃在以后可用于重建消化道的连续性[88]。这一术式下,Roux袢必须在胃囊下方几厘米处分开。切除腹腔淋巴结,离断胃左血管。余下的胃可充分活动。保留胃网膜,可以像处置常规患者一样制作管胃。根据外科医生的偏好,Roux袢可以被切除、重新吻合至胆胰袢或用于空肠造口[89,90]。最后,应将胃囊和远端食管放置于纵隔,并将管胃与胃囊缝合以便于从胸部取出[88]。食管切除的手术时机需要得到仔细规划——事实上,早期食管癌或对非手术治疗有良好反应的患者可首先接受减重方案,在减低BMI后接受食管切除术以降低术后并发症和死亡风险。然而,如前所述,在减重手术和食管切除术是可供选择的治疗选项时,还没有研究确定这些操作的最佳时机。

结论

肥胖食管癌患者接受食管切除术是安全可行的,可实现良好的肿瘤学和临床结局。精细的术前多学科规划和审慎的术后管理是降低不良结局、促进康复的关键条件。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Fernando A. M. Herbella, Rafael Laurino Neto and Rafael C. Katayama) for the series “How Can We Improve Outcomes for Esophageal Cancer?” published in Annals of Esophagus. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aoe.2020.02.02). The series “How Can We Improve Outcomes for Esophageal Cancer?” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. DM reports grants from Intuitive, other (consulting) from Urogen, other (consulting) from Johnson and Johnson, other (consulting) from Boston Scientific, outside the submitted work. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- World Health Organization. Key facts on obesity and overweight. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet 2016;387:1377-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nimptsch K, Pischon T. Body fatness, related biomarkers and cancer risk: an epidemiological perspective. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2015;22:39-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and oesphageal cancer. 2016 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Oesophageal-cancer-report.pdf

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and pancreatic cancer. 2012 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Pancreatic-cancer-report.pdf

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and liver cancer. 2015 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Liver-cancer-report.pdf

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and colorectal cancer. 2017 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Colorectal-cancer-report.pdf

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and breast cancer. 2017 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Breast-cancer-report.pdf

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and endometrial cancer. 2013 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Endometrial-cancer-report.pdf

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and kidney cancer. 2015 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Kidney-cancer-report.pdf

- Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, et al. Body fatness and cancer – viewpoint of the iARC working group. N Engl J Med 2016;375:794-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancers of the mouth, pharynx and larynx. 2018. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Mouth-Pharynx-Larynx-cancer-report.pdf

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and stomach cancer. 2016 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Stomach-cancer-report.pdf

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and gallbladder cancer. 2015 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Gallbladder-cancer-report.pdf

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and ovarian cancer. 2014 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Ovarian-cancer-report.pdf

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and prostate cancer. 2014 (Revised 2018). Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Prostate-cancer-report.pdf

- Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Courneya KS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on obesity and cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3568-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1625-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vainio H, Kaaks R, Bianchini F. Weight control and physical activity in cancer prevention: international evaluation of the evidence. Eur J Cancer Prev 2002;11:S94-100. [PubMed]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. GLOBOCAN 2018. Graph production: IARC. Available online: http://gco.iarc.fr/today

- Pohl H, Sirovich B, Welch HG. Esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence: are we reaching the peak? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:1468-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Imperial College London, Continuous Update Project Team Members. World Cancer Research Fund International Systematic Literature Review: the association between food, nutrition and physical activity and the risk of oesophageal cancer. 2015. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/oesophageal-cancer-slr.pdf

- Lagergren J. Influence of obesity on the risk of esophageal disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;8:340-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spechler SJ, Fitzgerald RC, Prasad GA, et al. History, molecular mechanisms, and endoscopic treatment of Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology 2010;138:854-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spechler SJ, Souza RF. Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med 2014;371:836-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morales CP, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Hallmarks of cancer progression in Barrett's oesophagus. Lancet 2002;360:1587-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryan AM, Duong M, Healy L, et al. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and esophageal adenocarcinoma: epidemiology, etiology and new targets. Cancer Epidemiol 2011;35:309-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Nyren O. Association between body mass and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:883-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chow WH, Blot WJ, Vaughan TL, et al. Body mass index and risk of adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:150-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol 2011;29:415-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:579-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2006;6:772-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein JH, Kao JY, Madanick RD, et al. Association of adiponectin multimers with Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2009;58:1583-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thompson OM, Beresford SA, Kirk EA, et al. Serum leptin and adiponectin levels and risk of Barrett’s esophagus and intestinal metaplasia of the gastroesophageal junction. Obesity 2010;18:2204-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doyle SL, Donohoe CL, Finn SP, et al. IGF-1 and its receptor in esophageal cancer: association with adenocarcinoma and visceral obesity. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:196-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Donohoe CL, Doyle SL, McGarrigle S, et al. Role of the insulin-like growth factor 1 axis and visceral adiposity in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg 2012;99:387-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greer KB, Thompson CL, Brenner L, et al. Association of insulin and insulin-like growth factors with Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2012;61:665-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garcia JM, Splenser AE, Kramer J, et al. Circulating inflammatory cytokines and adipokines are associated with increased risk of Barrett's esophagus: a case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:229-238.e3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nimptsch K, Steffen A, Pischon T. Obesity and oesophageal cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res 2016;208:67-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindkvist B, Johansen D, Stocks T, et al. Metabolic risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma: a prospective study of 580,000 subjects within the Me-Can project. BMC Cancer 2014;14:103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen ZM, Xu Z, Collins R, et al. Early health effects of the emerging tobacco epidemic in China. A 16-year prospective study. JAMA 1997;278:1500-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freedman ND, Abnet CC, Caporaso NE, et al. Impact of changing US cigarette smoking patterns on incident cancer: risks of 20 smoking-related cancers among the women and men of the NIH-AARP cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:846-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uppot RN, Sahani DV, Hahn PF, et al. Impact of obesity on medical imaging and image-guided intervention. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;188:433-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uppot RN, Sheehan A, Seethamraju R. Obesity and MR imaging. In: MRI hot topics. Malvern: Siemens Medical Solutions USA, 2008.

- Ng A, Smith G. Gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration of gastric contents in anesthetic practice. Anesth Analg 2001;93:494-513. [PubMed]

- Smith G, Ng A. Gastric reflux and pulmonary aspiration in anaesthesia. Minerva Anestesiol 2003;69:402-6. [PubMed]

- Brady M, Kinn S, Stuart P. Preoperative fasting for adults to prevent perioperative complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;CD004423 [PubMed]

- Salem MR, Khorasani A, Saatee S, et al. Gastric tubes and airway management in patients at risk of aspiration: history, current concepts, and proposal of an algorithm. Anesth Analg 2014;118:569-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knoth S, Weber B, Croll M, et al. Anaesthesiologic Techniques for Patients at Risk of Aspiration. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 2019;54:589-602. [PubMed]

- Rubinstein I, Zamel N, DuBarry L, et al. Airflow limitation in morbidly obese, nonsmoking men. Ann Intern Med 1990;112:828-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pelosi P, Croci M, Ravagnan I, et al. The effects of body mass on lung volumes, respiratory mechanics, and gas exchange during general anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1998;87:654-60. [PubMed]

- Salome CM, King GG, Berend N. Physiology of obesity and effects on lung function. J Appl Physiol 2010;108:206-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bahammam AS, Al-Jawder SE. Managing acute respiratory decompensation in the morbidly obese. Respirology 2012;17:759-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bucklin BA, Fernandez-Bustamante A. Chapter: Obesity and anesthesia. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, et al. Clinical anesthesia 7th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013:1274-93.

- Steier J, Lunt A, Hart N, et al. Observational study of the effect of obesity on lung volumes. Thorax 2014;69:752-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lugogo NL, Kraft M, Dixon AE. Does obesity produce a distinct asthma phenotype? J Appl Physiol 2010;108:729-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sutherland ER, Goleva E, King TS, et al. Cluster analysis of obesity and asthma phenotypes. PLoS One 2012;7:e36631 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Alwan A, Bates JH, Chapman DG, et al. The nonallergic asthma of obesity. A matter of distal lung compliance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:1494-502. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaw R, Michota F, Jaffer A, et al. Unrecognized sleep apnea in the surgical patient: implications for the perioperative setting. Chest 2006;129:198-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garg R, Singh A, Prasad R, et al. A comparative study on the clinical and polysomnographic pattern of obstructive sleep apnea among obese and non-obese subjects. Annals of Thoracic Medicine 2012;7:26-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh M, Liao P, Kobah S, et al. Proportion of surgical patients with undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea. Br J Anaesth 2013;110:629-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olson AL, Zwillich C. The obesity hypoventilation syndrome. Am J Med 2005;118:948-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chau EH, Lam D, Wong J, et al. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a review of epidemiology, pathophysiology, and perioperative considerations. Anesthesiology 2012;117:188-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pépin JL, Borel JC, Janssens JP. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: an underdiagnosed and undertreated condition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:1205-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Bustamante A, Hashimoto S, Serpa Neto A, et al. Perioperative lung protective ventilation in obese patients. BMC Anesthesiol 2015;15:56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Licker M, Diaper J, Villiger Y, et al. Impact of intraoperative lung-protective interventions in patients undergoing lung cancer surgery. Crit Care 2009;13:R41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang M, Ahn HJ, Kim K, et al. Does a protective ventilation strategy reduce the risk of pulmonary complications after lung cancer surgery?: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2011;139:530-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maslow AD, Stafford TS, Davignon KR, et al. A randomized comparison of different ventilator strategies during thoracotomy for pulmonary resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;146:38-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Unzueta C, Tusman G, Suarez-Sipmann F, et al. Alveolar recruitment improves ventilation during thoracic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2012;108:517-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Astle SM. Pain management in critically ill obese patients. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2009;21:323-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smit C, De Hoogd S, Brüggemann RJM, et al. Obesity and drug pharmacology: a review of the influence of obesity on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2018;14:275-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Bentre DJ, et al. Esophageal and Esophagogastric Junction Cancers, Version 2.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019;17:855-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bamgbade OA, Rutter TW, Nafiu OO, et al. Postoperative complications in obese and non-obese patients. World J Surg 2007;31:556-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Melis M, Weber JM, McLoughlin JM, et al. An elevated body mass index does not reduce survival after esophagectomy for cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:824-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scarpa M, Cagol M, Bettini S, et al. Overweight patients operated on for cancer of the esophagus survive longer than normal-weight patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2013;17:218-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang SS, Yang H, Luo JK, et al. The impact of body mass index on complication and survival in resected oesophageal cancer: a clinical-based cohort and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2013;109:2894-903. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mengardo V, Pucetti F, Mc Cormack O, et al. The impact of obesity on esophagectomy: a meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus 2018; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sgourakis G, Gockel I, Radtke A, et al. Minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy: meta-analysis of outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:3031-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Biere SSAY, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Maas KW, et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-lable, randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:1887-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fenton JR, Bergeron EJ, Coello M, et al. Feeding jejunostomy tubes placed during esophagectomy: are they necessary? Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:504-11; discussion 511-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kayani B, Okabayashi K, Ashrafian H, et al. Does obesity affect outcomes in patients undergoing esophagectomy for cancer? A meta-analysis. World J Surg 2012;36:1785-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ouattara M, D'Journo XB, Loundou A, et al. Body mass index kinetics and risk factors of malnutrition one year after radical oesophagectomy for cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:1088-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin L, Jia C, Rouvelas I, et al. Risk factors for malnutrition after oesophageal and cardia cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2008;95:1362-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin L, Lagergren J, Lindblad M, et al. Malnutrition after oesophageal cancer surgery in Sweden. Br J Surg 2007;94:1496-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin L, Lagergren P. Long-term weight change after oesophageal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2009;96:1308-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rossidis G, Browning R, Hochwald SN, et al. Minimally invasive esophagectomy is safe in patients with previous gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014;10:95-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marino KA, Weksler B. Esophagectomy after weight-reduction surgery. Thorac Surg Clin 2018;28:53-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nguyen NT, Tran CL, Gelfand DV, et al. Laparoscopic and thoracoscopic Ivor Lewis esophagectomy after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:1910-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ellison HB, Parker DM, Horsley RD, et al. Laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy for esophageal adenocarcinoma identified at laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016;25:179-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

王培宇

北京大学人民医院胸外科科研博士。从事肺癌、食管癌发病机制及诊断治疗的基础与临床研究。目前以第一作者在IJS、EJCTS、ASO等杂志发表SCI论文8篇,总IF为37.0。多次于ISDE、EACTS及全国胸心血管外科会议作发言和壁报交流。(更新时间:2021/7/27)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Amabile A, Carr R, Molena D. Esophagectomy for cancer in the obese patient. Ann Esophagus 2020;3:6.