Diagnosis and treatment of pseudoachalasia: how to catch the mimic

Introduction

Achalasia is a functional motility disorder of the esophagus characterised by failure of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation, aperistalsis in the body of the esophagus and normal or increased resting LES pressure (1). Most cases of achalasia are idiopathic in nature and related to the progressive loss of inhibitory neurons of the myenteric plexus within the esophageal wall (2,3). A small proportion of patients who are initially diagnosed with achalasia are eventually found to have an identifiable pathology driving this process and thus diagnosed as having secondary achalasia or “pseudoachalasia”.

The first documented observation of a likely case of pseudoachalasia was in 1919, when Howarth described two patients with gross esophageal dilatation without an obstructing luminal lesion, who were subsequently found to have small carcinomas in the wall of the abdominal esophagus at laparotomy (4). Ogilvie further described how malignant lesions of the gastric fundus could cause proximal esophageal dilatation and barium swallow appearances similar to “cardiospasm”, an early term for achalasia (5). Additional reports of gastric cancer underlying a diagnosis of cardiospasm came from Park and Asherson (6,7).

Distinguishing primary “idiopathic” achalasia from secondary pseudoachalasia remains challenging for clinicians. Both conditions present with similar symptoms, manometric findings and appearances on radiological investigations. In order to maximise the likelihood of correctly diagnosing pseudoachalasia, the term ‘idiopathic achalasia’, as with other idiopathic conditions, should be considered as a diagnosis of exclusion. Because pseudoachalasia is such a close mimic of idiopathic achalasia, patients should be considered as having an ‘achalasia-like syndrome’ until secondary causes for esophageal dysmotility have been considered and excluded. The importance of differentiating the two conditions cannot be understated given the vastly different management required for pseudoachalasia, not to mention the prognostic significance for the patient.

We describe an example case of pseudoachalasia seen in our clinical practice. This is followed by a review of the available literature and a discussion on the key issues raised, with particular focus on diagnostic risk factors for and management of this rare clinical entity.

Case presentation

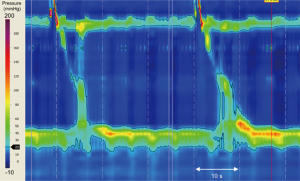

A 70-year-old woman presented to a peripheral centre with a three-month history of weight loss and progressive dysphagia to solids and liquids. An initial gastroscopy showed an esophagus of normal appearance with normal mucosa, but with significant resistance to passage of the gastroscope through the gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ). Cardia gastritis was visualised on retroflexion, which was biopsied and post-procedure histopathology confirmed gastritis. Following an esophageal high-resolution manometry (HRM), the differential diagnosis of achalasia was suspected (see Figure 1).

Treatment options were considered, and the patient was referred to our specialist centre and booked for a repeat endoscopic examination in preparation for a laparoscopic Heller myotomy.

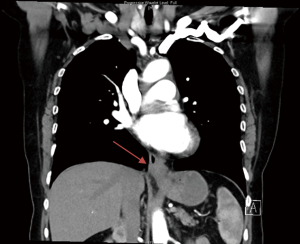

At the subsequent endoscopy, performed 6 weeks after the original, a tight GEJ was evident which could be traversed and a Siewert 3 GEJ adenocarcinoma was identified. The tumour extended from the cardia into the distal esophagus. A CT abdomen/pelvis was performed and can be seen in Figure 2. A diagnostic laparoscopy found a serosal positive malignancy with positive cytology. With a revised diagnosis, the patient received palliative chemotherapy for her gastric malignancy.

Literature review

Methods

Due to the rarity of the condition, it was anticipated that there would not be sufficient high-quality trials to conduct a formal systematic review regarding pseudoachalasia. Therefore, a literature review using Cochrane, Embase, Medline and grey literature was performed to identify diagnostic methodologies, assessment tools and treatment approaches used for pseudoachalasia. Studies were only included if they were written in English and described the use of manometry in the diagnosis of pseudoachalasia. All authors felt manometry to be an essential investigation to reliably confirm esophageal aperistalsis and impairment of LES relaxation (8). Studies were excluded if the publication represented a missed or longstanding case of idiopathic achalasia, or if a case of malignancy was likely to be secondary to the achalasia rather than causing the syndrome. Malignancy complicating long-standing achalasia is a well described phenomenon, but usually presents differently with longer history of dysphagia and the histological subtype is usually squamous tumours located in the mid-esophagus (9).

Results

Database searches and grey literature searches identified 1,520 manuscripts. After the elimination of duplicate and irrelevant results, 200 full-text articles were retrieved. Of these, 109 articles met eligibility criteria comprising 222 patients with pseudoachalasia. All studies were retrospective and the majority were individual case reports with a few case series described (see Table 1) (10-18). The average age of patients with pseudoachalasia, where stated, was 59.2 years old with a range from 1.5 to 88 years old. One hundred and nineteen patients were male and 66 were female, with the rest not stated. This corresponds to a 1.8:1 male-to-female ratio. The most common underlying cause was esophago-gastric malignancy, which was cited in 86 cases (39%). Sixty-three patients were excluded, for either not having manometry (60 patients) or lacking a clinical presentation that was truly one of pseudoachalasia. Previous reviews of pseudoachalasia have included patients who did not undergo a manometry study. This partly explains why there are fewer cases of gastro-esophageal cancer reported in our current review than counted previously.

Table 1

| Author | Year of publication | Name of article | Journal | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ponds FA | 2017 | Diagnostic features of malignancy-associated pseudoachalasia | |

18 |

| Ellingson TL | 1995 | Iatrogenic achalasia | |

14 |

| Liu W | 2002 | The pathogenesis of pseudoachalasia: a clinicopathologic study of 13 cases of a rare entity | |

13 |

| Campo SM | 2013 | Pseudoachalasia: a peculiar case report and review of the literature | |

11 |

| Katzka DA | 2012 | Achalasia secondary to neoplasia: a disease with a changing differential diagnosis | |

11 |

| Stylopoulos N | 2002 | Development of achalasia secondary to laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication | |

7 |

| Tucker HJ | 1978 | Achalasia secondary to carcinoma: manometric and clinical features | |

7 |

| Kahrilas PJ | 1987 | Comparison of pseudoachalasia and achalasia | |

6 |

| Khan A | 2011 | Potentially reversible pseudoachalasia after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding | |

6 |

Discussion

Epidemiology

Idiopathic achalasia remains a rare disease. A 2017 study looking at the incidence of achalasia in South Australia found an incidence of 2.3–2.8 cases per 100,000 per year (19). This study specifically excluded patients with a potential secondary cause of achalasia. Other studies of idiopathic achalasia, performed since the introduction of high-resolution esophageal manometry, quote an incidence ranging from 0.3–1.8 per 100,000 per year (20-22). Estimating the incidence and prevalence of pseudoachalasia is more challenging. Most estimates of the incidence of secondary causes for achalasia amongst all patients with achalasia-like syndromes are based on relatively small case series. In these case series, pseudoachalasia reportedly accounts for 1.5–5.4% of all achalasia cases, thereby representing a small fraction of an already rare condition (10,11,14,23-25).

Etiologies

Pseudoachalasia can be a manifestation of several malignant and benign pathologies. The most common underlying lesion is a primary malignant neoplasm of the proximal stomach or distal esophagus; responsible for between 50–75% of cases of pseudoachalasia (10,11,25). A wide variety of other malignancies can be complicated by the development of pseudoachalasia, either through direct invasion from contiguous structures or local mass effect from metastatic deposits. Malignancies reported to cause pseudoachalasia in this way are described in the Table 2 (26-42). Extremely rarely, pseudoachalasia is reported in association with paraneoplastic syndromes (14,43). Such syndromes mostly occur in the setting of neuroendocrine and squamous cell carcinomas of the lung (14). Benign causes of pseudoachalasia are less common and include certain operative procedures, non-operative trauma, as well as a variety of benign pathologies summarised in Table 3 (15,44-54).

Table 2

| Malignancies reported to cause pseudoachalasia |

| Gastro-esophageal adenocarcinoma |

| Lung cancer (Inc. adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, SCC and small cell carcinoma) |

| Malignant mesothelioma |

| Breast cancer |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma |

| Sarcoma |

| Esophageal SCC |

| Cholangiocarcinoma |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| Prostate cancer |

| Renal cell carcinoma |

| Bladder urothelial cell carcinoma |

| Cervical SCC |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Hepatic SCC |

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia Type 2b |

| Gastric lymphoma |

| Pharyngeal SCC |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Table 3

| Cause | Number of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Malignant | |

| Gastro-esophageal adenocarcinoma | 89 (40.1) |

| Lung cancer (Inc. adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, SCC and small cell) | 16 (7.2) |

| Malignant mesothelioma | 9 (4.1) |

| Breast cancer | 8 (3.6) |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 7 (3.2) |

| Sarcoma | 3 (1.4) |

| Other malignancies | 19 |

| Benign | |

| Post-operative complications | 38 (17.3) |

| Leiomyoma | 8 (3.6) |

| Amyloidosis | 5 (2.3) |

| Neurofibromatosis | 4 (1.8) |

| Systemic sclerosis | 4 (1.8) |

| Other benign conditions | 12 (5.45) |

Pathogenesis

Whilst the conditions known to cause pseudoachalasia have been identified, the mechanism behind the characteristic motility abnormalities that mimic idiopathic achalasia is poorly understood. It is likely that because of the many potential causative pathologies, the pathogenesis of pseudoachalasia is not uniform across all cases.

Two mechanisms put forward for pseudoachalasia seen in malignancy are direct mechanical obstruction and submucosal infiltration, with subsequent destruction of neuronal cells of the myenteric plexus. Mechanical obstruction is often quoted as a cause of pseudoachalasia, however the characteristic finding on endoscopy in pseudoachalasia is the lack of an obvious stenosing lesion or malignant stricture and a macroscopically normal mucosa.

In many cases of pseudoachalasia, submucosal infiltration of the myenteric plexus by tumour cells producing secondary neuronal inhibition of esophageal peristalsis is the proposed mechanism for inducing an achalasia-like syndrome. This hypothesis is supported by findings from histological examinations, demonstrating massive submucosal tumour infiltration replacing the ganglion cells and the absence of a stenosing mucosal lesion (55-59).

Another proposed mechanism for pseudoachalasia secondary to metastatic malignancy is a localised peripheral neuropathy of the vagus nerve (27,60). This association of pseudoachalasia with damage to the main trunk of the vagus nerve would be in keeping with one of the proposed mechanisms for pseudoachalasia following operative and non-operative trauma (1). Contrary to this explanation is the observation in animal models that achalasia-like manometry findings are only reproducible if both vagi are transected in the cervical region or around the hila of the lungs. Typical manometric findings for achalasia-like syndrome did not develop when more distal esophageal vagal branches near the lower sphincter were interrupted (61).

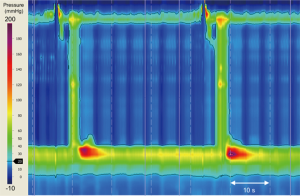

Several operations may inadvertently give rise to the development of pseudoachalasia. Current procedures include Nissen fundoplication, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB), and hiatus hernia repair (13,62,63). Dysmotility can occur even many years after the index operation (Figure 3) (63-65). Proposed mechanisms implicated in the development of pseudoachalasia following upper gastro-intestinal (GI) surgery include: fibrosis around the GEJ; post-operative edema; stricture formation; malformation of the fundal wrap, disruption of the fundal wrap and recurrent hiatus hernia (66). Poulin et al. have suggested a categorisation system of achalasia-like dysmotility seen after upper GI surgery:

- type 1 represents synchronous primary achalasia misdiagnosed as gastro-esophageal reflux disease before intervention,

- type 2 is true secondary achalasia, secondary to iatrogenic fibrosis, edema or stricture and

- type 3 is metachronous primary achalasia developing years after surgery without any evidence of esophageal pathology relating to the previous surgery (65).

Nissen fundoplication and LAGB are the procedures most often implicated in post-surgical pseudoachalasia (18,67). There is also experimental evidence in a feline model that reversible achalasia can be induced, by placing a constrictive band around the distal esophagus of animals (68). This raises the possibility that the mechanical effect of an improperly constructed fundoplication wrap or subsequent fibrosis as well as bariatric surgery can cause pseudoachalasia.

Other reported causes of pseudoachalasia which are not related to direct mechanical compression or vagal involvement are paraneoplastic syndromes, usually in association with lung cancer, and sarcoidosis (43,46).

In pseudoachalasia, regardless of the initial underlying pathology, the end result is a functional obstruction of the distal esophagus due to failure of LES relaxation with resultant esophageal dilatation and stasis. Ultimately, this GEJ outflow obstruction leads to an altered neuromuscular response in attempt to overcome the functional blockage. If GEJ outflow obstruction continues unabated, and is not relieved, this eventually leads to failure of normal esophageal motility and thus symptomatology and manometric findings consistent with achalasia arises (12,69).

Clinical features

Pseudoachalasia presents in an identical manner to idiopathic achalasia with progressive dysphagia to solids and liquids, retrosternal pain, regurgitation of undigested foods and weight loss (11). This makes differentiating the two diagnoses based on symptoms alone impossible. Several authors have identified symptoms that may be more pronounced in patients with pseudoachalasia. Patients who present at an older age (≥55-year-old); have shorter duration of dysphagia (≤12 months); and have pronounced weight loss (≥10 kg) are at higher risk of pseudoachalasia versus idiopathic achalasia (25,70,71). These criteria are highly sensitive, but only moderately specific. When the diagnostic risk factor of difficulty passing the endoscopy through the GEJ is added to the above criteria, then the presence of two or more of these risk factors increases the likelihood of pseudoachalasia, with a specificity of 77–99.7% and sensitivity of 28–50%. However low prevalence of this condition amongst patients with manometric findings of achalasia, means these risk factors have a low positive predictive value (72).

Duration of symptoms

The onset of dysphagia in idiopathic achalasia is typically more insidious with only 16% presenting in the first year of symptom onset (73). In a cohort of 5 patients with pseudoachalasia, Tracey and Traube found patients with pseudoachalasia had symptomatic dysphagia for a much shorter time course compared to 10 patients with idiopathic achalasia (72). Kahrilas et al. found in a comparison of six patients with pseudoachalasia versus 167 with primary achalasia, that all patients with pseudoachalasia had symptoms for less than 10 months compared with 5% of primary achalasia patients with symptoms <12 months (25). Nevertheless, this 5% represents eight patients, which is more than the total pseudoachalasia cases in their series. This report confirms the suggested discriminating features have a low predictive value.

Weight

Significant weight loss (>10 kg) is a clinical feature often quoted to be more common in pseudoachalasia. Pronounced weight loss (>10 kg) is unusual in idiopathic achalasia. However, it is well-recognised that even with idiopathic achalasia, significant weight loss can be seen. This is reflected in the inclusion of weight loss as a component of the Eckardt score for clinical severity of achalasia (74). For Tracey et al.’s cohort, overall weight loss was similar between patients with pseudoachalasia and controls. However, the rate of weight loss (as determined by weight loss and duration of dysphagia) was significantly higher in the pseudoachalasia group which may make this a more sensitive indicator.

Age

Adults with pseudoachalasia are often older than patients with idiopathic achalasia. Bessent et al. reports the average presenting age of patients with achalasia is 40-year-old, whereas it is 62-year-old for patients with gastro-esophageal cancer (most common etiology for pseudoachalasia) (55). Only 15% of patients with idiopathic achalasia present older than 60 years of age (73). Woodfield et al., in a series of 10 patients and Ponds et al. with a series of 18 patients, show similar findings for age at presentation (16,75). Whilst older age at presentation should raise the suspicion of pseudoachalasia, exceptions to this are reported. Several cases of pseudoachalasia secondary to gastric adenocarcinoma have occurred in adolescents as young as 15- and 16-year-old (76,77).

Investigations

The diagnosis of pseudoachalasia remains challenging and multiple modalities often fail to obtain a correct diagnosis in a timely fashion. Initial investigation findings mimic primary achalasia and biopsy findings are frequently negative. A high degree of suspicion is required to persist with further investigations, despite all initial evidence suggesting a primary esophageal motility disorder. If there is anything unusual about the patient’s presentation raising the possibility of a malignancy, further testing and even repeated investigations should be performed.

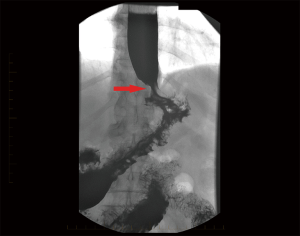

The appearances on barium swallow for achalasia and pseudoachalasia are highly similar or identical. Figure 4 demonstrates a barium swallow from a patient with a junctional adenocarcinoma presenting as pseudoachalasia. Specific features that may suggest underlying pseudoachalasia include a longer length of the narrowed distal esophageal segment (>3.5 cm) and narrower diameter (<4 cm) of the esophageal body compared with idiopathic achalasia (75).

Endoscopic examination of the oesophagus and stomach is mandatory in the investigation of dysphagia. In cases of pseudoachalasia there is no intra-luminal occlusive lesion and the mucosa is macroscopically normal although some nodularity can be observed (78). Multiple endoscopies and biopsies of the mucosa will often fail to identify an underlying malignancy (36,79-82). In idiopathic achalasia, while the manometric resting tone of the LES is often increased, there is usually no resistance to the passage of an endoscope through the GEJ. Conversely, a common finding in patients with pseudoachalasia is difficulty passing the endoscope through the GEJ (72,79,83,84). This is usually due to an underlying malignant cause. Retroflexion of the endoscope in the stomach to fully inspect the gastric fundus and cardia is essential, to try and visualise potential causative lesions (78).

Manometry remains the gold standard test for diagnosing achalasia, by proving the presence of impaired GEJ relaxation and esophageal aperistalsis (8,85). The introduction of esophageal high-resolution manometry (HRM) in combination with esophageal pressure topography (EPT) has allowed for objective and highly reproducible measurements to be taken. In a series reported by Menin et al., a pattern was observed with conventional manometry in 11 patients with pseudoachalasia secondary to gastric tumours that was characterised by high-amplitude, repetitive, non-progressive contractions. This pattern was described as similar to that of “vigorous achalasia” (86). While vigorous achalasia is now an outdated term in the era of HRM, this represented an early effort to subgroup achalasia phenotypes based on esophageal pressure patterns. More recently, a retrospective evaluation of manometric patterns using HRM in patients with pseudoachalasia, revealed HRM pressure patterns often fail to neatly identify with an achalasia subtype based on the Chicago Classification (87). This study comparing manometric features of achalasia with pseudoachalasia secondary to esophago-gastric adenocarcinoma found compartmentalised pressurisation confined to the distal esophagus was a consistent finding in the pseudoachalasia patients. The authors propose this finding may be a useful clue to differentiate idiopathic and pseudoachalasia, while recognising further studies are needed (87).

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) provides a highly useful modality for the identification of occult tumours likely to be causing pseudoachalasia. This investigation offers several advantages to endoscopy alone in the setting of pseudoachalasia. Firstly, the esophageal mucosa is usually macroscopically normal in cases of pseudoachalasia, belying the usual causative malignancy infiltrating the wall of the organ. This submucosal pathology is better visualised with EUS, revealing abnormal submucosal thickening often not readily appreciated on computed tomographic (CT) imaging (82). Additionally, EUS combined with fine-needle aspiration of abnormal lesions can provide a histological diagnosis for the underlying pathology, where previous endoscopic mucosal biopsies have failed (88-90). If there is difficulty passing the endoscope through the GEJ at the initial study, or nodularity/ulceration is seen at this area on passage of the scope, then it might be prudent to use EUS at the repeat endoscopy (91). A study found that EUS performed in addition to HRM for patients with esophageal motility disorders, identified clinically significant lesions in nine out of 62 patients (15%) (92). This included two cases of esophagogastric carcinoma, one case of sarcoidosis and one of leiomyoma.

A CT of the chest and abdomen is undertaken at some point during the diagnostic work-up for most patients with pseudoachalasia. As an imaging modality it has limited sensitivity for detecting tumours around the GEJ, even those with significant local invasion (14,93). There are, therefore, limitations in the ability of this modality to confidently distinguish between pseudoachalasia and achalasia. In one study CT only identified the underlying malignancy in two of eight patients with achalasia (94). Further, it incorrectly diagnosed a patient with achalasia as having an underlying malignancy. Esophageal wall thickening is commonly seen in both achalasia and pseudoachalasia. This same study found that symmetrical esophageal wall thickening <10 mm was likely to be achalasia; whereas asymmetrical esophageal wall thickening >10 mm (especially at the GEJ) was observed in pseudoachalasia patients. In another study CT was only able to detect a mass at the GEJ in 40% of patients who were eventually found to have a tumour masquerading as achalasia [109].

In summary, in order to not miss a case of pseudoachalasia, if a patient with manometric pressure patterns indicating an achalasia-like syndrome has had a normal endoscopy carefully consider the duration of dysphagia and severity of weight loss as well as previous GI surgery. When a patient, especially one over the age of 55, has a short symptomatic duration and pronounced weight loss, repeat endoscopic review of the GEJ anatomy with biopsies, as well as EUS is recommended. If EUS is negative, then CT chest/abdomen or other cross-sectional imaging should be undertaken to try and identify any underlying pathology (95). This combination of investigation modalities is likely to catch the vast majority of cases of pseudoachalasia and will allow such patients to be managed appropriately.

Management

The management of pseudoachalasia consists of treating the underlying cause driving the motility disorder where possible. This is the ideal, as there are reports of the achalasia-like syndrome resolving following successful treatment of the inciting pathology (33,86). Where malignancy is the cause, surgical resection of the primary gastro-intestinal tumour, as well as chemotherapy and radiotherapy to distant metastases has in some settings achieved resolution of the esophageal dysmotility (33,86,96,97). Unfortunately, the majority of the patients will have pseudoachalasia secondary to an esophageal or gastric cancer that is usually locally advanced at diagnosis, in no small part due to the difficulties in achieving an accurate diagnosis. Due to the locally advanced nature of many tumours presenting as pseudoachalasia, cure is often not possible. Management in this setting focuses on best palliation including resolution or reduction of dysphagia. In cases associated with benign conditions or in the setting of localised malignancy, the management of pseudoachalasia revolves around the treatment of the inciting etiology. In particular benign pseudoachalasia as a complication of previous esophago-gastric surgery, usually resolves following surgical revision with resolution of dysmotility (65,66).

Patients whose pseudoachalasia is initially misdiagnosed as idiopathic achalasia, will often be subjected to pneumatic balloon dilatation. This will provide either temporary relief or no benefit at all in the patient with dysphagia and pseudoachalasia secondary to malignancy (26,88). Moreover, this treatment can delay the diagnosis of the underlying malignancy and there is a higher risk of pneumatic dilatation causing esophageal perforation in this setting (24). If pneumatic balloon dilatation is attempted in the presence of a cardia tumour, the true diagnosis can be alluded to when the endoscopist notices a lack of distensibility, with the balloon failing to reach proper outline under pressure, as visualised using fluoroscopy (29,88,98,99). Balloon dilatation has some success however in patients whose pseudoachalasia is secondary to benign conditions, such as vagal damage and operative trauma (12,100). Such patients will have a pre-existing history of identifiable trauma, usually from operative procedures around the GEJ or involving the vagus nerve. Other benign etiologies of pseudoachalasia treated successfully with balloon dilatation are amyloidosis and pseudoachalasia in the setting of neurofibromatosis (45,101,102).

Whilst botulinum toxin (Botox) injection of LES is an effective, proven treatment of idiopathic achalasia, by reducing LES pressure and cholinergic tone, it does not have any place in the management pseudoachalasia and will not provide any sustained symptomatic improvement (27,50). Patients who may theoretically respond to Botox are those where destruction of myenteric plexus nerves either directly or through a paraneoplastic syndrome (14).

Patients undergoing surgery involving manipulation around the GEJ often experience dysphagia in the early post-operative period. Such patients have also been shown to have significantly reduced primary peristalsis on manometry which typically improves after 3 months (103). Those who do not improve despite conservative treatment and who have dysmotility confirmed with manometry should undergo a full suite of standard investigations (endoscopy, manometry and fluoroscopy) with a view to revisional surgery to correct the identified problem. If still no improvement occurs, they should have their surgery revised if possible (10,63,104). During revision surgery some authors have also performed a concurrent Heller myotomy (64,104). In such cases it is unclear whether the revision itself or the myotomy was the deciding factor in each patient’s improvement. Procedures causing pseudoachalasia where revision of the procedure has been documented to reverse the dysmotility disorder are Nissen fundoplication and LAGB (13,63,105). In the case of Nissen fundoplication revision, usually a Dor fundoplication is performed after taking the old wrap down in order to treat the pseudoachalasia whilst preventing recurrence of reflux disease (63). With a LAGB, the first step in management is to remove the fluid from the band and if this fails to improve symptoms then to proceed to component removal, and importantly any fibrotic tissue encasing the band must also be removed (13,64,106).

Conclusions

The recognition and timely management of pseudoachalasia remains a challenge for clinicians due to the close resemblance to idiopathic achalasia. The etiology of most cases of secondary achalasia remains a variety of primary and metastatic malignant neoplasms. Clinical features of older age at presentation, pronounced weight loss and shorter duration of dysphagia prior to presentation as well as the feature on endoscopy of difficulty passing the scope through the GEJ should raise clinical suspicion of a secondary cause despite these features still having a low positive predictive value. A repeat endoscopy should be undertaken if there is diagnostic doubt. If doubt still lingers, EUS should be considered, or where not available, CT chest/abdomen by a highly experienced radiologist. Management will vary, depending on the likely underlying cause. The overarching management aim in pseudoachalasia is the successful treatment of the underlying cause, as this has often shown to reverse the esophageal dysmotility.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Sarah Thompson) for the series “Achalasia” published in Annals of Esophagus. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aoe.2020.03.03). The series “Achalasia” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Shah RN, Izanec JL, Friedel DM, et al. Achalasia presenting after operative and nonoperative trauma. Dig Dis Sci 2004;49:1818-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spechler SJ, Castell DO. Classification of oesophageal motility abnormalities. Gut 2001;49:145-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldblum JR, Whyte RI, Orringer MB, et al. Achalasia. A morphologic study of 42 resected specimens. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:327-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Howarth W. Discussion on Dilatation of the Oesophagus without Anatomical Stenosis. Proc R Soc Med 1919;12:64. [Crossref]

- Ogilvie H. The early diagnosis of cancer of the oesophagus and stomach. Br Med J 1947;2:405-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park WD. Carcinoma of cardiac portion of the stomach. Br Med J 1952;2:599-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asherson N. Cardiospasm; intermittent; an initial manifestation of carcinoma of the cardia. Br J Tuberc Dis Chest 1953;47:39-40. [PubMed]

- Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. American Gastroenterological A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology 2005;128:207-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Camara-Lopes LH. Carcinoma of the esophagus as a complication of megaesophagus. An analysis of seven cases. Am J Dig Dis 1961;6:742-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Campo SM, Zullo A, Scandavini CM, et al. Pseudoachalasia: A peculiar case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013;5:450-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gockel I, Eckardt VF, Schmitt T, et al. Pseudoachalasia: a case series and analysis of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005;40:378-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ellingson TL, Kozarek RA, Gelfand MD, et al. Iatrogenic achalasia. A case series. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995;20:96-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan A, Ren-Fielding C, Traube M. Potentially reversible pseudoachalasia after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:775-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katzka DA, Farrugia G, Arora AS. Achalasia secondary to neoplasia: a disease with a changing differential diagnosis. Dis Esophagus 2012;25:331-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu W, Fackler W, Rice TW, et al. The pathogenesis of pseudoachalasia: a clinicopathologic study of 13 cases of a rare entity. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:784-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ponds FA, van Raath MI, Mohamed SMM, et al. Diagnostic features of malignancy-associated pseudoachalasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:1449-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tucker HJ, Snape WJ Jr, Cohen S. Achalasia secondary to carcinoma: manometric and clinical features. Ann Intern Med 1978;89:315-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stylopoulos N, Bunker CJ, Rattner DW. Development of achalasia secondary to laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 2002;6:368-76; discussion 77-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duffield JA, Hamer PW, Heddle R, et al. Incidence of Achalasia in South Australia Based on Esophageal Manometry Findings. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:360-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sadowski DC, Ackah F, Jiang B, et al. Achalasia: incidence, prevalence and survival. A population-based study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22:e256-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gennaro N, Portale G, Gallo C, et al. Esophageal achalasia in the Veneto region: epidemiology and treatment. Epidemiology and treatment of achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 2011;15:423-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim E, Lee H, Jung HK, et al. Achalasia in Korea: an epidemiologic study using a national healthcare database. J Korean Med Sci 2014;29:576-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abubakar U, Bashir MB, Kesieme EB. Pseudoachalasia: A review. Niger J Clin Pract 2016;19:303-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Kishk SM, et al. Radiologic amyl nitrite test for distinguishing pseudoachalasia from idiopathic achalasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986;146:21-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kahrilas PJ, Kishk SM, Helm JF, et al. Comparison of pseudoachalasia and achalasia. Am J Med 1987;82:439-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Borst JM, Wagtmans MJ, Fockens P, et al. Pseudoachalasia caused by pancreatic carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;15:825-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bholat OS, Haluck RS. Pseudoachalasia as a result of metastatic cervical cancer. JSLS 2001;5:57-62. [PubMed]

- Eaves R, Lambert J, Rees J, et al. Achalasia secondary to carcinoma of prostate. Dig Dis Sci 1983;28:278-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Branchi F, Tenca A, Bareggi C, et al. A case of pseudoachalasia hiding a malignant pleural mesothelioma. Tumori 2016;102. [PubMed]

- Ghoshal UC, Sachdeva S, Sharma A, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma presenting with severe gastroparesis and pseudoachalasia. Indian J Gastroenterol 2005;24:167-8. [PubMed]

- Goldschmiedt M, Peterson WL, Spielberger R, et al. Esophageal achalasia secondary to mesothelioma. Dig Dis Sci 1989;34:1285-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cuthbert JA, Gallagher ND, Turtle JR. Colonic and oesophageal disturbance in a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2b. Aust N Z J Med 1978;8:518-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis JA, Kantrowitz PA, Chandler HL, et al. Reversible achalasia due to reticulum-cell sarcoma. N Engl J Med 1975;293:130-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kline MM. Successful treatment of vigorous achalasia associated with gastric lymphoma. Dig Dis Sci 1980;25:311-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kotoulas C, Galanis G, Yannopoulos P. Secondary achalasia due to a mesenchymal tumour of the oesophagus. Eur J Surg Oncol 2000;26:425-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lahbabi M, Ihssane M, Sidi Adil I, et al. Pseudoachalasia secondary to metastatic breast carcinoma mimicking radiation stenosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2012;36:e117-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manela FD, Quigley EM, Paustian FF, et al. Achalasia of the esophagus in association with renal cell carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86:1812-6. [PubMed]

- Nensey YM, Ibrahim MA, Zonca MA, et al. Peritoneal mesothelioma: an unusual cause of esophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:1617-20. [PubMed]

- Moorman AJ, Oelschlager BK, Rulyak SJ. Pseudoachalasia caused by retroperitoneal B-cell lymphoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:A32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonavina L, Fociani P, Asnaghi D, et al. Synovial sarcoma of the esophagus simulating achalasia. Dis Esophagus 1998;11:268-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roark G, Shabot M, Patterson M. Achalasia secondary to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol 1983;5:255-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Lago I, De-la-Riva S, Subtil JC, et al. Pseudoachalasia secondary to infiltration of the pillars of the diaphragm by an urotelial tumor: Diagnostic approach with endoscopic ultrasound. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2015;107:121-2. [PubMed]

- Hejazi RA, Zhang D, McCallum RW. Gastroparesis, pseudoachalasia and impaired intestinal motility as paraneoplastic manifestations of small cell lung cancer. Am J Med Sci 2009;338:69-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boruchowicz A, Canva-Delcambre V, Guillemot F, et al. Sarcoidosis and achalasia: a fortuitous association? Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:413-4. [PubMed]

- Costigan DJ, Clouse RE. Achalasia-like esophagus from amyloidosis. Successful treatment with pneumatic bag dilatation. Dig Dis Sci 1983;28:763-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dufresne CR, Jeyasingham K, Baker RR. Achalasia of the cardia associated with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Surgery 1983;94:32-5. [PubMed]

- Colarian JH, Sekkarie M, Rao R. Pancreatic pseudocyst mimicking idiopathic achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:103-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beqari J, Lembo A, Critchlow J, et al. Pseudoachalasia Secondary to Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;103:e517-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deng B, Gao XF, Sun YY, et al. Case report: successful resection of a leiomyoma causing pseudoachalasia at the esophagogastric junction by tunnel endoscopy. BMC Gastroenterol 2016;16:24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fishman VM, Parkman HP, Schiano TD, et al. Symptomatic improvement in achalasia after botulinum toxin injection of the lower esophageal sphincter. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:1724-30. [PubMed]

- Woods CA, Foutch PG, Waring JP, et al. Pancreatic pseudocyst as a cause for secondary achalasia. Gastroenterology 1989;96:235-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tamada R, Sugimachi K, Yaita A, et al. Lymphangioma of the esophagus presenting symptoms of achalasia--a case report. Jpn J Surg 1980;10:59-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin JS, Yu YR, Chiou EH, et al. Intramural esophageal bronchogenic cyst mimicking achalasia in a toddler. Pediatr Surg Int 2017;33:119-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park RH, McKillop JH, Belch JJ, et al. Achalasia-like syndrome in systemic sclerosis. Br J Surg 1990;77:46-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bessent CT, Lopez CA, Cocco AE. Carcinoma of the E G junction mimicking achalasia. Md State Med J 1973;22:47-50. [PubMed]

- Kolodny M, Schrader ZR, Rubin W, et al. Esophageal achalasia probably due to gastric carcinoma. Ann Intern Med 1968;69:569-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maleki MF, Fleshler B, Achkar E, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction presenting as achalasia. Cleve Clin Q 1979;46:137-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serebro HA, Venkatachalam B, Prentice RS, et al. Possible pathogenesis of motility changes in diffuse esophageal spasm associated with gastric carcinoma. Can Med Assoc J 1970;102:1257-9. [PubMed]

- Rock LA, Latham PS, Hankins JR, et al. Achalasia associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol 1985;80:526-8. [PubMed]

- Shulze KS, Goresky CA, Jabbari M, et al. Esophageal achalasia associated with gastric carcinoma: lack of evidence for widespread plexus destruction. Can Med Assoc J 1975;112:857-64. [PubMed]

- Carveth SW, Schlegel JF, Code CF, et al. Esophageal motility after vagotomy, phrenicotomy, myotomv. and mvomectomv in dogs. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1962;114:31-42. [PubMed]

- Duntemann TJ, Dresner DM. Achalasia-like syndrome presenting after highly selective vagotomy. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:2081-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai CN, Krishnan K, Kim MP, et al. Pseudoachalasia presenting 20 years after Nissen fundoplication: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;11:96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Losh JM, Sanchez B, Waxman K. Refractory pseudoachalasia secondary to laparoscopically placed adjustable gastric band successfully treated with Heller myotomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017;13:e4-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poulin EC, Diamant NE, Kortan P, et al. Achalasia developing years after surgery for reflux disease: case reports, laparoscopic treatment, and review of achalasia syndromes following antireflux surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 2000;4:626-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parrilla P, Aguayo JL, Martinez de Haro L, et al. Reversible achalasia-like motor pattern of esophageal body secondary to postoperative stricture of gastroesophageal junction. Dig Dis Sci 1992;37:1781-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiesner W, Hauser M, Schob O, et al. Pseudo-achalasia following laparoscopically placed adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg 2001;11:513-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Little AG, Correnti FS, Calleja IJ, et al. Effect of incomplete obstruction on feline esophageal function with a clinical correlation. Surgery 1986;100:430-6. [PubMed]

- Song CW, Chun HJ, Kim CD, et al. Association of pseudoachalasia with advancing cancer of the gastric cardia. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;50:486-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ponds FA, Moonen A, Smout A, et al. Screening for dysplasia with Lugol chromoendoscopy in longstanding idiopathic achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:855-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rozman RW Jr, Achkar E. Features distinguishing secondary achalasia from primary achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:1327-30. [PubMed]

- Tracey JP, Traube M. Difficulties in the diagnosis of pseudoachalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:2014-8. [PubMed]

- Reynolds JC, Parkman HP. Achalasia. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1989;18:223-55. [PubMed]

- Eckardt VF, Aignherr C, Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology 1992;103:1732-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woodfield CA, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, et al. Diagnosis of primary versus secondary achalasia: reassessment of clinical and radiographic criteria. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;175:727-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aichbichler BW, Eherer AJ, Petritsch W, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma mimicking achalasia in a 15-year-old patient: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;32:103-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fabian E, Eherer AJ, Lackner C, et al. Pseudoachalasia as First Manifestation of a Malignancy. Dig Dis 2019;37:347-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parkman HP, Cohen S. Malignancy-induced secondary achalasia. Dysphagia 1994;9:292-6. [PubMed]

- Iascone C, Maffi C, Pascazio C, et al. Recurrent gastric carcinoma causing pseudoachalasia: case report. Dis Esophagus 2000;13:87-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hejazi RA, McCallum RW. Treatment of refractory gastroparesis: gastric and jejunal tubes, botox, gastric electrical stimulation, and surgery. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2009;19:73-82. vi. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moonka R, Pellegrini CA. Malignant pseudoachalasia. Surg Endosc 1999;13:273-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faigel DO, Deveney C, Phillips D, et al. Biopsy-negative malignant esophageal stricture: diagnosis by endoscopic ultrasound. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:2257-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Portale G, Costantini M, Zaninotto G, et al. Pseudoachalasia: not only esophago-gastric cancer. Dis Esophagus 2007;20:168-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gottmann U, Brinkkoetter PT, Hoeger S, et al. Atorvastatin donor pretreatment prevents ischemia/reperfusion injury in renal transplantation in rats: possible role for aldose-reductase inhibition. Transplantation 2007;84:755-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg SP, Burrell M, Fette GG, et al. Classic and vigorous achalasia: a comparison of manometric, radiographic, and clinical findings. Gastroenterology 1991;101:743-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Menin R, Fisher RS. Return of esophageal peristalsis in achalasia secondary to gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci 1981;26:1038-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sutton RA, Gabbard SL. High-resolution esophageal manometry findings in malignant pseudoachalasia. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bryant RV, Holloway RH, Nguyen NQ. Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the evaluation of pseudoachalasia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:1128. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jia Y, McCallum RW. Pseudoachalasia: Still a Tough Clinical Challenge. Am J Case Rep 2015;16:768-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ziegler K, Sanft C, Friedrich M, et al. Endosonographic appearance of the esophagus in achalasia. Endoscopy 1990;22:1-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carlson DA, Kahrilas PJ. Editorial: when to be suspicious of malignancy-associated pseudoachalasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:198. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krishnan K, Lin CY, Keswani R, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound as an adjunctive evaluation in patients with esophageal motor disorders subtyped by high-resolution manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:1172-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chak A, Canto M, Gerdes H, et al. Prognosis of esophageal cancers preoperatively staged to be locally invasive (T4) by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS): a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc 1995;42:501-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carter M, Deckmann RC, Smith RC, et al. Differentiation of achalasia from pseudoachalasia by computed tomography. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:624-8. [PubMed]

- Eckardt AJ, Eckardt VF. Current clinical approach to achalasia. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:3969-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fredens K, Tottrup A, Kristensen IB, et al. Severe destruction of esophageal nerves in a patient with achalasia secondary to gastric cancer. A possible role of eosinophil neurotoxic proteins. Dig Dis Sci 1989;34:297-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldin NR, Burns TW, Ferrante WA. Secondary achalasia: association with adenocarcinoma of the lung and reversal with radiation therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 1983;78:203-5. [PubMed]

- Bennett JR. Not . . . achalasia. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288:93-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim HM, Chu JM, Kim WH, et al. Extragastroesophageal Malignancy-Associated Secondary Achalasia: A Rare Association of Pancreatic Cancer Rendering Alarm Manifestation. Clin Endosc 2015;48:328-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chuah SK, Kuo CM, Wu KL, et al. Pseudoachalasia in a patient after truncal vagotomy surgery successfully treated by subsequent pneumatic dilations. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:5087-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suris X, Moya F, Panes J, et al. Achalasia of the esophagus in secondary amyloidosis. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:1959-60. [PubMed]

- Foster PN, Stewart M, Lowe JS, et al. Achalasia like disorder of the oesophagus in von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis. Gut 1987;28:1522-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Myers JC, Jamieson GG, Wayman J, et al. Esophageal ileus following laparoscopic fundoplication. Dis Esophagus 2007;20:420-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonavina L, Bona D, Saino G, et al. Pseudoachalasia occurring after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and crural mesh repair. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2007;392:653-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lipka S, Katz S. Reversible pseudoachalasia in a patient with laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013;9:469-71. [PubMed]

- Cruiziat C, Roman S, Robert M, et al. High resolution esophageal manometry evaluation in symptomatic patients after gastric banding for morbid obesity. Dig Liver Dis 2011;43:116-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Barnett DR, Balalis GL, Myers JC, Devitt PG. Diagnosis and treatment of pseudoachalasia: how to catch the mimic. Ann Esophagus 2020;3:16.